I loved watching Statler and Waldorf on the Muppets in the 1970’s. They were my jam for sure. They made comedy out of hating on the other Muppets performing on stage, like this simple jab:

Waldorf: They aren’t half bad.

Statler: Nope, they’re ALL bad!

It was great comedy for a few reasons. They were Muppets and performers themselves. Their skit added a layer of playful self-deprecation. And their comments were clearly made to provoke yet another laugh from the audience, joy and happiness.

About the same time as the Muppets were entertaining America, Farrah Fawcett’s iconic swimsuit poster was published. Like millions of other teens, I scraped up a few bucks, bought it and hung it on my bedroom wall until it became tattered after a few years. Everyone loved her. Until they didn’t. She’s not that pretty, they said. She’s not even the best of Charlie’s Angels, they said. It isn’t even a bikini, they said. I’ve seen better posters, they said. I witnessed this phenomenon that I barely understood then, if at all. When people succeed, a bandwagon of supporters begins to grow. But at a certain point, the tide turns, and a certain percentage of people seem compelled to be the naysayers and tear them down. The haters gonna hate. You can count on it.

And we have seen it with hundreds of people, often entertainers and athletes, like Muhammad Ali, Taylor Swift, Tom Brady, and most recently, NCAA Basketball star Caitlin Clark. I suppose psychologists can cite several reasons why some of us hate these successful people: insecurity, feelings of inadequacy, self-doubt, concerns about unfairness or just frustration.

Some of you may want to debate me on who is hated and why. But in the words of Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, “I would prefer not to.” I have heard all about deflate-gate, but this is more about hate-gate. Or is it?

Wait. Are you wondering if I am going to connect this to strategic communications? Don’t be a hater. Of course, I am. I began this with interpersonal communications examples in order to segue into how these evolve into a common strategic communications mistake. I have spent my fair share of time trying to defend these successful individuals, especially Farrah Fawcett, to no avail. Until Caitlin Clark, I wasted too much time. I think Caitlin Clark and women’s basketball has become a juggernaut success story. But I have no energy left to debate the haters, the adversaries. Clark and women’s basketball will be more than fine despite a small but vocal group of haters.

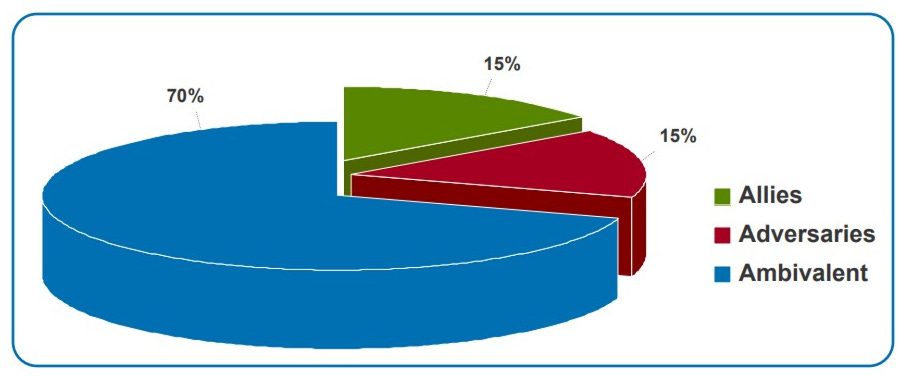

The adversaries. See, every topic, issue, event, or reputation typically faces three distinctly different groups: Allies, Ambivalent, and Adversaries. We can quibble about the percentages because I haven’t met the scientist or numerologist who can defend any precise number. However, anecdotally and from experience, we can probably agree that the extremes are typically lower numbers. There are a few who loves us, a few who hate us, and a vast majority in the middle.

Farrah Fawcett taught us that it is a waste of time to put our energy into the adversaries. As a quick aside, it is ironic that many years later when she was suffering from and ultimately died from anal cancer that the haters all seemed to disappear. Anyway, most of us have worked for a boss who wanted us to go after the adversaries. Bring them down. Fight the good fight. Yet, when we do that, we lose sight of the sweet spot, the ambivalent. This group is larger in numbers and either undecided or at least malleable. The ambivalent can make a difference. Let’s put our energy there.

The Muppet performers never worried about pleasing Statler and Waldorf (well, maybe Fozzie Bear got a little frustrated). The haters gonna hate. Instead of worrying about them, go after the ambivalent. That’s the ticket right there. And the show must go on.

This editorial is dedicated to Farrah Fawcett and Bartleby the Scrivener.

###